Last month (on 6th April 2025) I preached at Sherbourne Community Church in Coventry. I was very pleased to be asked to do so. Below is the text of my sermon (I am sorry not to have posted it sooner; I was delayed by health problems and other issues).

To be clear: this is the text I wrote beforehand but in practice I deviated from the wording at times and added in a couple of extra comments. But the substance is much the same.

The sermon followed two Bible readings:

John 12, 1-8

Philippians 3, 3-14

Some parts of the gospels are really weird. Some of us have got so used to reading the gospels that we can forget how odd parts of them would sound if we hadn’t read them before. And we have a great example with the passage from John 12 that we heard earlier.

Here we have Mary pouring a load of expensive perfume over Jesus’ feet. This story appears in various forms in other gospels too, although there are significant variations – about who the woman is who does this, and about how she does it. But the idea of a woman physically pouring oil on Jesus seems to have been widely recognised in one form or another.

And what a strange thing it is to do. And in John’s version of the story, Judas pops up says that it would be better to have sold the ointment and given the money to the poor. And if you’re like me, you might find yourself thinking, Didn’t Judas have a point?

Okay, John tells us that Judas had an ulterior motive, that he really wanted to embezzle the money. But if he had been going to give it to the poor, would that not have been a better use for this ointment than chucking it all over Jesus? If we believe Judas – and we might not, of course – then the ointment could have been sold for 300 denarii. That would have been the best part of a year’s wages for someone on a low income in that society. Are there not better things that could have been done with it?

Jesus responds to Judas’ comment by reminding his disciples that they can continue to support the poor. Compassion for the poor out is not simply a one-off act for unusual moments like this. “You always have the poor with you,” he says.

Outrageously, there are still Christians who misuse this line to argue that Christians should not try to end poverty. This is ridiculous. Jesus was reminding his disciples of the situation they were in and would continue to be in for the foreseeable future. He was not opposing attempts to end poverty. Poverty is not something created by God. It is created by humans. Indeed, nowadays we know the world has enough to feed all the people in it, if we organised things differently. We – humans – created poverty and we – humans – can end it.

Jesus’ comment – like all his comments – was made in a specific context. Jesus thanks Mary for her faith in him. And the writer of the gospel uses it to make a point about Jesus: the ointment is to anoint him for his burial. Because Jesus would soon die, executed in unimaginable pain by the forces of the Roman Empire.

For much of John’s Gospel, Jesus seems to be very focused on his upcoming death. I find it hard to imagine how this would have affected his day-to-day thoughts. And here we have a connection with the second reading – the reading from Philippians that we heard.

Paul wrote the Letter to the Philippians while he was in prison, while he awaited to find out whether he would be executed. I find that Paul’s letters tend to make a lot more sense when we realise that he wrote them to particular people at particular times. He didn’t know that people would be reading them 2,000 years later!

Paul’s mental anguish seems clear in his letter to the Philippian Christians. He wrestles with thoughts about whether he will live or die, about his desire to be with Jesus clashing with his hope of living longer and continuing to serve Christ’s people on Earth. At times he seems to fear for the communities he has founded that he may be leaving behind. Here, perhaps, we encounter Paul at his most vulnerable. Philippians contrasts with the finely crafted theological nuance of Paul’s letter to the Romans, with the passionate anger of his letter to the Galatians, with his frustrated attempts to resolve conflicts in his letters to the Corinthians. In Philippians, Paul seems very aware that he might be at the end of his life.

This sheds light on the words that we heard earlier. We hear Paul listing things he could boast about, particularly when it comes to religion. He has always been an observant and religious Jew, he says. He was blameless under the law. He persecuted Christians. All the things his critics boast about, he could boast about too!

But then he tells us that none of this matters. “Whatever gains I had, these I have come to regard as loss because of Christ,” he tells us.

Paul’s religious observances would not save him. His zeal and law-keeping would not save him. His persecution of people with different beliefs would not save him. He can be saved only through the grace of God, by the love of God that Jesus reveals.

But 2,000 years later, we can still make the mistake of relying on religious observances. Of course, it is good to go to church, to pray, to come together as Christ’s people to worship and talk and share Communion. It can be helpful to observe Lent and be disciplined in prayer. These are good and helpful things to do. We can honour God through them. But they will not save us. We do not have eternal life and salvation because of these things. We do not have them because of any our actions but because of God’s action through Jesus.

As Paul puts it the Philippian Christians, he does not have a righteousness of his own but only the righteousness that comes from God.

Some years ago, I helped a friend sell off his possessions at a car boot sale. We had a successful morning and as we were packing up, we found that one of the few items that we had left was a kite. We were approached by a couple with a small child, who was very upset. He had hoped to buy a kite he had seen on a nearby stall, but when he went back to it, the kite had been sold. Now he noticed that we had a kite. But he didn’t have the money to pay for it. Perhaps we were feeling generous because our sales had gone well, but we gave the child the kite. His tears turned to smiles, and his parents were very grateful.

“We’ve made a small child very happy,” I said to my friend afterwards. He replied, “Yes. If there’s a God, chalk that up!”.

Now my friend is an atheist, though perhaps he was having a moment of doubt. But he gave the kite to the child because he thought it was a good and compassionate thing to do, to make someone happy, not because he was trying to get into heaven. If I had given the kite to the child out of a desire for heaven, would that not make me more selfish than my atheist friend? I hope and think that God approved of our gift to the child, but I did not do it in an attempt to earn points with God or to buy my way to salvation.

In theory, as Christians, and particularly as Protestant Christians, we believe that salvation comes through the grace of God in Jesus, not through what we do. But do we really dare to believe this? That God’s love is so big, so wide, so mind-bendingly transformative, that God’s grace in Jesus can save us from our sins and bring us eternal life?

This is so hard to believe! A lot of people, including a lot of Christians, talk as if eternal life will come to us because of our actions. Some Christians talk as if they think they will be saved by believing exactly the right things about Jesus, about the Bible, about theology. But that’s just another way of trusting in our actions rather than in God. We are saved by Christ, not by Christianity. Some people seem to think that LGBT+ people are excluded from God’s salvation, as if we are saved by heterosexuality.

If I thought any of these things to be true, I would be very worried about my own chances of being saved. I am bisexual. Some of my beliefs might, for all I know, be completely mistaken. And if I am to be judged on my actions, I honestly am far from sure that my good deeds would outweigh my bad ones. But Paul reminds us repeatedly that there is no salvation in such things but only in turning to God’s love and forgiveness.

If we believe in salvation by God’s grace then does that mean that how we live doesn’t matter? Does this mean we can carry on day-to-day, conforming to the world around us and simply waiting for God’s salvation when we die?

No, I don’t think it does. Because putting our trust in Jesus means that we have a different starting point, a different focus, from the dominant values of this world. And that means that we will live differently, or at least that we will seek to live differently, while being prepared to turn to God and ask for forgiveness even if we repeatedly fail.

This takes us back to the text of Paul’s Letter to the Philippians. I hope you’ll bear with me if I tell you a personal story.

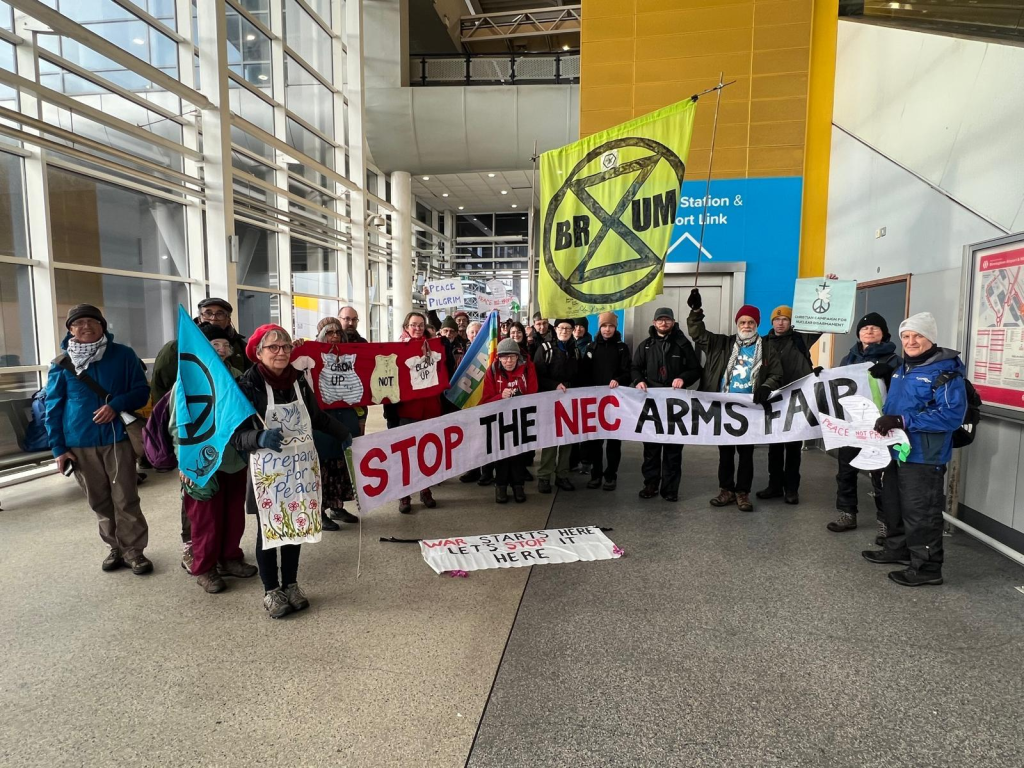

Twelve years ago, I was at a protest outside the London arms fair. The DSEI arms fair, which takes place every two years in east London, involves arms companies doing deals with representatives of governments from around the world, including some of the world’s most vicious and aggressive regimes. In 2013, I joined with other Christians in blocking an entrance to the arms fair by kneeling in prayer. When we refused to move, we were arrested and, at the police station I was the first of the group to be processed. As I was checked in, I asked if I could have a Bible to read in my cell. A policeman reached to a shelf behind the desk and gave me the Bible that they kept there.

I was in the cell by the time my friend Chris was processed. He also asked for a Bible. “You want a Bible too!” said a surprised police officer. “The last bloke asked for a Bible.” They managed to find another Bible for Chris, but by the time the third person was processed, the station was running out of Bibles. When the third person, James, was processed, they told him they would try to find a Bible, but he was already in the cell by the time they did so. One of the officers went to James’ cell and told him that he’d only managed to find a New Testament. “That’s okay,” said James. “I hope you’re not going to keep me here long enough to read both testaments”.

As I sat in my cell with my Bible. I decided to read Philippians. This was because I knew that Paul had written it in prison. Perhaps this was a bit arrogant on my part. It would be ridiculous to compare my own situation to Paul’s. He was in prison indefinitely awaiting a likely death sentence. I had just been locked up for a few hours. Nonetheless, the calming and encouraging words that Paul wrote in prison had a positive effect on me.

But they might not have done. Reading Paul’s words about how we are saved by Jesus alone, I could have concluded that the actions I had taken at the arms fair were not worthwhile. Resisting the arms trade couldn’t earn me points with God, couldn’t get me into heaven. Shouldn’t I just sit quietly at home, live the same as everyone around me, and wait for eternal life to come because of my faith in Jesus?

No, I couldn’t. Of course, not all of us are called to do things that lead us to be arrested. Following Jesus and his call on our lives takes many different forms for many different people. Some who respond most faithfully to Jesus live quiet lives of compassion that can easily go unnoticed – but they are not unnoticed by God.

As Paul writes in Philippians, “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection”. I pray that God will give me more ability to trust in Jesus, to really trust in him, which at times I find so hard. To trust Jesus rather than in my own efforts or in the dominant attitudes of the world.

It seems to me that the more we trust in Jesus, the more we have to live differently. The more we trust in Jesus, the less trust we will place in the idols that dominate this world – the idols of money and markets and military might – systems that humans have created but which we find ourselves bowing down and serving. If we trust in the Kingdom of God that Jesus proclaims then we cannot trust in the powers of this world. Psalm 146 reminds us, “Put not your trust in the powerful, mere mortals in whom there is no help”.

Following Jesus is not about a list of rules. It is about a different starting-point, rooted in the love that Jesus reveals. This leads us back to that passage from John’s Gospel. Should Mary have sold the ointment and given the money to the poor? Perhaps that would have been just as good an option – or even a better option – than pouring it over Jesus. But in that moment, she acted on her faith in Jesus by anointing him in preparation for his death. And Jesus thanks her, Jesus praises her, for the actions that come from her faith.

We are called to live with our focus on God, not to be saved but in response to being saved by Jesus. We are not saved by our actions, our religious observances or our correct opinions, but only by the love of God that we encounter in Jesus. That love enables us, as Paul writes in Romans 12, to refuse to conform to the world around us and instead to allow ourselves to be transformed by God’s love. This is the love revealed in Jesus, a love that can transform us, a love that can transform the world.